Go on, admit it. You saw that ‘World’s Fastest Indian’ movie all those years ago and you now secretly dream of taking a bike to the salt flats and twisting the throttle until it won’t twist any more. Just you, the salt, the sky and the speed. The endless speed. Well, today’s bike was made by a bunch of crazy Aussies who’ve clearly got too much salt in their diet and a big problem with impulsive behavior; if you can call two years of hard work and untold thousands of dollars ‘impulsive’. Introducing the new Australian speed record-breaking Triumph Salt Racer.

We were lucky enough to speak to Nigel Harvey, the team’s talking head, while he was still washing the salt and red dust out of his beard after arriving back in Melbourne. “Our team was basically myself, Paul Chiodo, who’s the Managing Director of Triumph Australia as well as a Motorbike Dealership called Peter Stevens Motorcycles, and Ross Osbourne who is the man behind Supacustom, a local custom bike builder with a strong reputation. There was also Cliff Stovall who is Triumph Australia’s Technical Manager and someone with a very extensive racing background, and Andrew Hallam who is one of Australia’s best race engine builders with Superbike and Isle of Man TT experience. It was a massive group effort.”

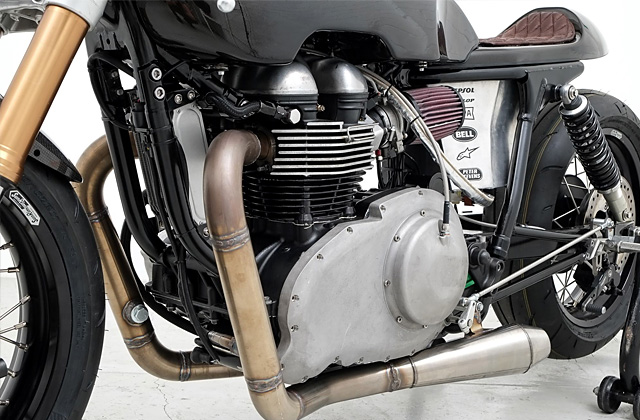

We were lucky enough to speak to Nigel Harvey, the team’s talking head, while he was still washing the salt and red dust out of his beard after arriving back in Melbourne. “Our team was basically myself, Paul Chiodo, who’s the Managing Director of Triumph Australia as well as a Motorbike Dealership called Peter Stevens Motorcycles, and Ross Osbourne who is the man behind Supacustom, a local custom bike builder with a strong reputation. There was also Cliff Stovall who is Triumph Australia’s Technical Manager and someone with a very extensive racing background, and Andrew Hallam who is one of Australia’s best race engine builders with Superbike and Isle of Man TT experience. It was a massive group effort.”“The bike started life as a 2008 Thruxton with fuel injection. We began with a complete strip-down and a rear frame chop. We they extended the swing arm and swapped the front end for a Daytona 675 set-up. Rear shockers are Ikon 7613 units. The original tank was removed and replaced with a bespoke carbon fibre shell to house the bikes wiring, with a the new tank fabricated from Aluminum by Ross that was mounted under the seat. The front brakes were removed, and the original lever now controls the rear brake. The rearsets were also made by Ross and sit pretty close to the rear axle.”

“The engine was bored and stroked to 1000cc and the crank was fully worked, ground and heavy metal balanced. Conrods are the originals as Hallam sees them as a good unit; they were shot peened and polished for strength, but the pistons and barrels were replaced with Wiseco parts. The head is where most of the time went; it was ported to within an inch of its life with a drastic increase in both inlet and exhaust valve size. In fact, the inlet valve seats now eat into the head gasket.”

“Fuel and air are delivered by a set of 64mm throttle bodies that are effectively double the size of the originals, and require a crazy billet adaptor to work. A custom valve bucket and shim set-up was developed to deal with the extreme profile of the Hallam camshafts. The gases are expelled through a set of custom 2.5 inch headers that Ross developed at Supacustom using stainless tube with Cone Engineering mufflers at the noisy end.”

The clutch is hydraulic with cover assembly from the guys at Mule motorcycles and the plates are Barnett Kevlar units. Other bits include a Power Commander, GPS data-logger, a lambda live air fuel meter, a Mule oil cooler and a DLRA-mandated steering damper manufactured by Scott. The boys got a dyno’d 110bhp at the rear wheel while running on a ‘mild’ blend of 102 octane and methanol. That’s up from a factory 39bhp, or an increase of almost 300% of the original. Wow.

The clutch is hydraulic with cover assembly from the guys at Mule motorcycles and the plates are Barnett Kevlar units. Other bits include a Power Commander, GPS data-logger, a lambda live air fuel meter, a Mule oil cooler and a DLRA-mandated steering damper manufactured by Scott. The boys got a dyno’d 110bhp at the rear wheel while running on a ‘mild’ blend of 102 octane and methanol. That’s up from a factory 39bhp, or an increase of almost 300% of the original. Wow.The team started the build in 2013 with a mind to get the bike onto the salt in time for the Dry Lake Racers Australia 2014 event, held in late March. Alas, the sheer size of the project meant that they were to wait until this year to tread the crystals. South Australia’s Lake Gairdner is Bonneville’s Down Under twin and is renowned for its ‘fast’ salt conditions. But there’s a flip-side to that blessing – the lake’s location is just south of absolutely bloody nowhere.

Then two weeks ago, the team loaded up a bunch of 4WDs with a trailer for the bike and a caravan. And when they say loaded, they mean loaded. “There’s not a lot out there. It’s basically a time warp that’s typical of the Aussie outback. If we thought we’d need it, we took it. TIG welders. Push bikes. Generators. 850 liters of water. Booze. We had to be entirely self-sufficient for a week and that’s all part of the fun.”

“Getting to the lake is an effort in itself,” says Nigel with a touch of weariness. “It’s a two-day trip over 1500 kilometres (900 miles), the last leg of which is on a red dirt road that rattles, cars, bikes and trailers to death. The red dust gets into absolutely everything. All trailers are taped up, all bikes are wrapped in plastic but it still gets in. And then once you hit the lake itself, the salt takes over. It’s a constant battle against nature, and one you’re bound to lose.”

“Getting to the lake is an effort in itself,” says Nigel with a touch of weariness. “It’s a two-day trip over 1500 kilometres (900 miles), the last leg of which is on a red dirt road that rattles, cars, bikes and trailers to death. The red dust gets into absolutely everything. All trailers are taped up, all bikes are wrapped in plastic but it still gets in. And then once you hit the lake itself, the salt takes over. It’s a constant battle against nature, and one you’re bound to lose.”Of course, that’s not the only issue with being so far from civilisation. The inherent danger of world record speeds means that should you have an off, even a mild one, the only way to get medical help is by calling Australia’s legendary Royal Flying Doctor Service.

“Arriving there is like landing on the moon. It’s like some ancient being has moved all the scenery to another location. You can see how people could lose their grip on reality out there. And the 10˙C (50˙F) nights followed by the 40˙C (104˙F) days makes simple things much more challenging. There’s no shade at all.”

The lake is also a national park and traditional Aboriginal land, so there are more than a few interested parties to contend with. Both the Aboriginal elders and the park rangers are rightfully concerned about a bunch of speed freaks with too much horsepowers and not enough common sense tearing giant gashes into what is considered to be sacred ground. In fact, the elders insist that the salt remains white to ward off bad luck. “Everything that goes onto the salt has to have its own tarpaulin to ensure the salt isn’t stained or polluted. Bikes. Cars. Buses. Toilets. Everything.”

The lake is also a national park and traditional Aboriginal land, so there are more than a few interested parties to contend with. Both the Aboriginal elders and the park rangers are rightfully concerned about a bunch of speed freaks with too much horsepowers and not enough common sense tearing giant gashes into what is considered to be sacred ground. In fact, the elders insist that the salt remains white to ward off bad luck. “Everything that goes onto the salt has to have its own tarpaulin to ensure the salt isn’t stained or polluted. Bikes. Cars. Buses. Toilets. Everything.”“You’re in my house now!” – Animal, Race Director

‘Animal’ is the boss of the salt, and he runs the show. “He’s straight out of a Mad Max movie,” says Nigel. “When we first arrived, he stuck his head through the car window and shouted “You’re in my house now!” before laughing hysterically. Later, when heading out to the pits on the scooter I asked him if he had any advice for first-timers. ‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘Don’t fall in any big fucken holes.” Australian humour. It takes some getting used to.

Yet despite his appearances, Animal runs a pretty tight ship. “Any hooning or burn outs would get you thrown out of the event,” says Nigel. “And protecting the salt isn’t just talk. Every vehicle is cleaned of red dust with leaf blowers before it’s allowed on the salt. Then they are cleaned of salt on the way home. Protecting the lake isn’t something they take lightly.”

Then comes the main act – going bloody fast. The bike uses the ‘short’ track, which is 4 miles in length. And being an American-born sport, all distances and speeds are measured in imperial units. There’s a strict scrutineering process and a novice briefing to scare the cocky newbies, and then you’re at Animal’s mercy; a series of increasing fast “licensing” runs to satisfy the boss that you’re mentally and mechanically sound. They also allow teams to test out the machines without the pressure to go all out, straight out of the box. After all, where else could you test top speeds like these?

“The third day was our big one. After we were happy with our set-up, we went for it. The ultimate run was as amazing as it was nerve-racking. Our GPS recorded a top speed of 157 mph.” That’s 4mph over Sir Allan Cathcart’s world record set at Bonneville in the same class. But then the speed gods decided that they’d had enough fun and the parallel twin engine gave up the ghost, belching a cloud of whitish blue engine oil turned to smoke down the length of the course. Game over. “The best we can tell, it either couldn’t get enough oil or it couldn’t get enough fuel. We did a quick rip-down afterwards, but a full analysis will tell all”. The final speed through the traps was 149.626mph, a new Australian record for the Modified Fuel 1000cc class.

“Go outside. Start your bike. Run it at full throttle for 60 seconds. Let us know how that turns out for you.”

The truth is that speeds and conditions like this spell death for most engines. The real challenge for the teams is just keeping things in one piece. “Everyone wants to get out there on the first day. Then on the second day, the engines begin to pop. On day three 40% of the field is gone, and by the fourth day there’s only a few teams on the salt. In fact, most people were just kicking back and drinking beer.”

The truth is that speeds and conditions like this spell death for most engines. The real challenge for the teams is just keeping things in one piece. “Everyone wants to get out there on the first day. Then on the second day, the engines begin to pop. On day three 40% of the field is gone, and by the fourth day there’s only a few teams on the salt. In fact, most people were just kicking back and drinking beer.”We’ve heard the phrase ‘sacrifices to the god of speed’ before, but it’s only now that we really understand it. If your sole intention was to be an internal combustion serial killer, it seems you couldn’t do much better than to invent salt flat racing.

“As with most racing, it’s a massive learning curve. The salt and dust get into everything – engines included. Then there’s the traction issues on the salt and the tall gearing that’s required to get a bike up to speed. It’s a black art that’s impossible to test until you’re out there. There’s the wind, the death wobbles and the ballast that’s required to keep the bikes stable. And all this in the middle of a desert that’s baking you during the day and freezing you at night.”

“As with most racing, it’s a massive learning curve. The salt and dust get into everything – engines included. Then there’s the traction issues on the salt and the tall gearing that’s required to get a bike up to speed. It’s a black art that’s impossible to test until you’re out there. There’s the wind, the death wobbles and the ballast that’s required to keep the bikes stable. And all this in the middle of a desert that’s baking you during the day and freezing you at night.”Despite the trials and tribulations, it’s easy to tell the boys are infatuated. “We’ll be back next year, no doubt about it. And if that goes well, well who knows… the only way to set a FIM ratified record is at Bonneville,” says Nigel, smiling. Then he gets a little reflective. “After all the work we’d done, seeing the bike on the salt at 7am for the sunrise on the big day was a bit of a surreal experience. Easily the coolest thing I’ve ever been involved in. It was amazing.”

Our thoughts, exactly. God speed for next year, boys.